As COVID-19 continues to unfold, museums and archives are putting out calls for people to share their “stories” of what life is like during the pandemic. I suspect the majority of contributions will be either written reflections, digital photographs, or video clips. At the end of this arc, it’s likely that many of these stories will have at least an undercurrent of trauma.

Which means, a lot of archivists are going to be thrown into processing large volumes of traumatic material for the first time in their careers. What kind of plans are institutions implementing to handle the appraisal and description of these collections?

In my early career, I struggled to understand why certain days left me feeling burned out and overwhelmed because the impact of vicarious trauma was less known outside counseling settings. Over time, I developed a range of practices and I thought I’d take a moment to share one of them. It doesn’t negate the impact of vicarious trauma but it does reduce it to a more manageable level.

Like a lot of archivists, we work on long-range projects mixed with daily information requests in a continuous cycle. We used to rely on an Excel spreadsheet to track projects but we’re now using Airtable so we can link tables with different types of data; the benefit is it allows us to visualize our workload through groupings and filters.

As you can see from this screenshot, this filter of my week looks like a typical project tracker. The unique feature here is the “Trauma” column on the right.

The “Trauma” column refers to the amount of potential trauma I expect from any given project. The core idea is to limit your exposure. The structure that works best for me is:

- No more than two hours a day with high trauma items

- No more than four hours a day with moderate trauma items

I don’t blend those either so it’s frequently either working on a project with high or moderate levels and switching to low level work for the balance of the day. After using this method for a while, it becomes fairly intuitive, with the tracker merely helping me check that I’m not soaking down too much trauma.

The perceived level comes from experience and is specific to me. The benefit of a shared tracker for a department like mine is that everyone can set their own risk level. Which brings me to an important point: vicarious trauma does not impact people in the same way or from the same source; so being able to identify the type of material that could be problematic for you is an important part of this process.

If you currently use a project tracker this is an easy way to structure your day in a way that could help to minimize the impact. I know it sounds like a common sense trick, and it is, but I’m often surprised by colleagues who spend an entire day working with traumatic records and then don’t understand why they feel so crappy at the end of the day.

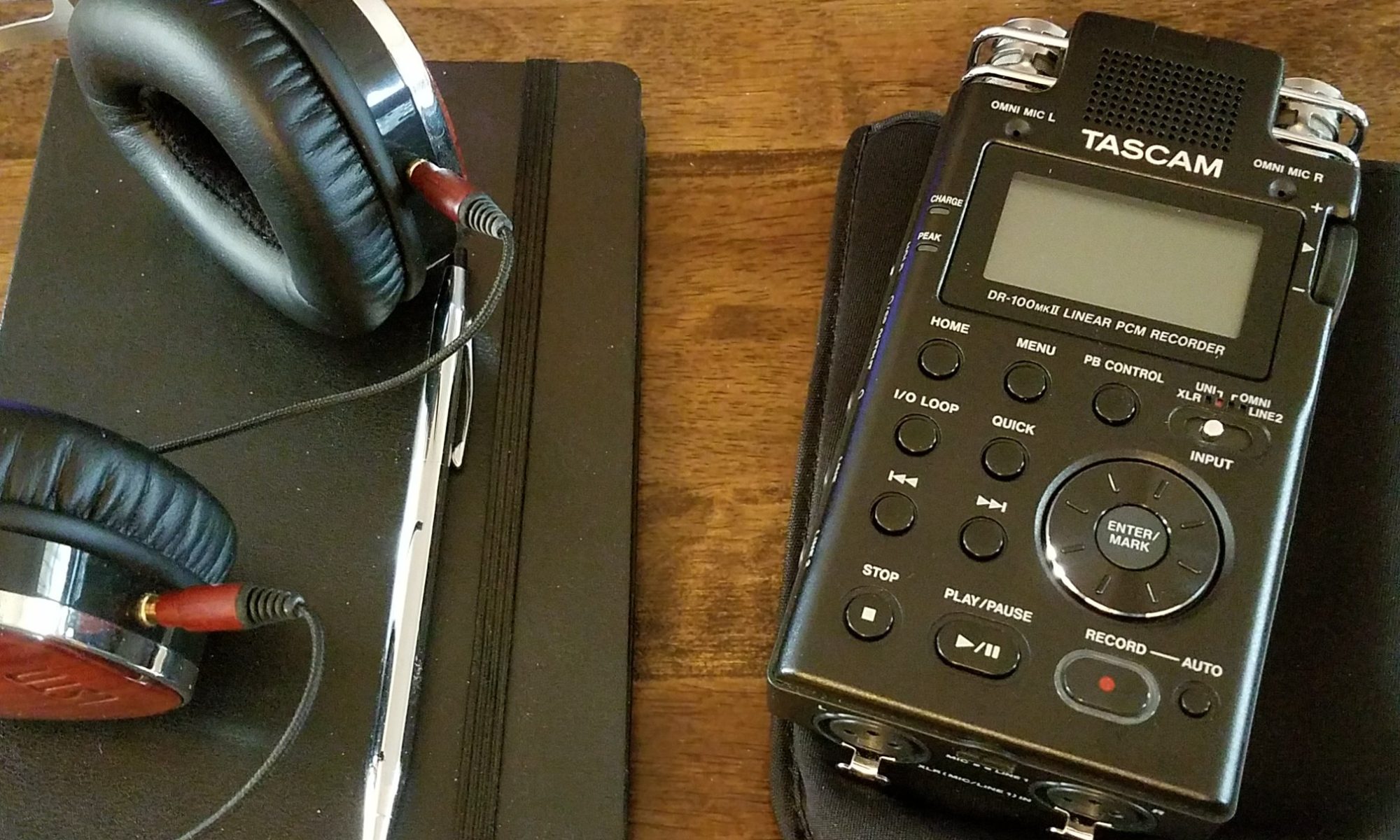

I would also be remiss if I didn’t say: if you’re new to working with this kind of material and feeling overwhelmed you should seek the help of a professional counselor. I saw one during my early oral history work and his advice on decompressing from those intense, emotionally heavy interviews continues to be indispensable.

If you think this might be helpful please use it. If you adopt this method into something different that you think works better let me know, I’m always trying to improve the way we manage our workload.